Many places in Nebraska are named after Native Americans, including our state. Nebraska gets its name from the Oto-Missourias. It is from two Oto-Missouria words “Ni-Brathge” (nee BRAHTH-gay) which means “water flat.” This name came from the Platte River which flows through the state and at some places moves so slowly and calmly that it is flat. The Omaha also claim origins for “Nebraska” as they share a common Siouan language base.

Many places in Nebraska are named after Native Americans, including our state. Nebraska gets its name from the Oto-Missourias. It is from two Oto-Missouria words “Ni-Brathge” (nee BRAHTH-gay) which means “water flat.” This name came from the Platte River which flows through the state and at some places moves so slowly and calmly that it is flat. The Omaha also claim origins for “Nebraska” as they share a common Siouan language base.

To learn more about the history of Native Americans in Nebraska and their challenges with the white man, read “I Am A Man” by Joe Starita and “An Unspeakable Sadness” by David J. Wishart.

To learn more about Nebraska Tribal history, check out the NCIA website at indianaffairs.state.ne.us.

The Oto-Missouria, Omaha and Pawnee Indians were the three main tribes that occupied the area of Southeast Nebraska. The Ponca were located in Northeast Nebraska. The Ioway and Sac & Fox also had a presence in Southeast Nebraska.

“In 1800, there were at least 14,000 Native Americans living in what is now the eastern half of Nebraska. These included, at a minimum: 10,000 Pawnee, 2,000 Omaha, 1,000 Oto-Missouria and 900 Ponca. Their territory covered more than 30,000,000 acres of land. One hundred years later, only 1,203 Omaha and 229 Ponca remained in their homelands and their territory was little more than 200,000 acres. The others had been moved to reservations in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). The Native Americans received an average of 10 cents an acre for the land that became Nebraska. By 1900 the immigrants had so changed the landscape that it was barely recognizable to the old Indians who had lived through it all.” From David Wishart’s book “An Unspeakable Sadness.”

Now the face of all the land is changed and sad. The living creatures are gone. I see the land desolate, and I suffer unspeakable sadness. Sometimes I wake in the night and feel as though I should suffocate from the pressure of this awful feeling of loneliness. White Horse, Omaha August 13, 1912.

Oto-Missouria Indians

Article credit: From the January/February 1984 issue of NEBRASKAland magazine

The Oto and Missouria are two of the four tribes that speak Chiwere dialects of the Siouxan family of languages. Before contact with the white man, the Oto and Missouria, along with the two

The Oto and Missouria are two of the four tribes that speak Chiwere dialects of the Siouxan family of languages. Before contact with the white man, the Oto and Missouria, along with the two

other Chiwere segments, the Winnebagos and Iowas, probably made up a single nation living near the Great Lakes.

The separation of the Oto and Missouria from the Iowa and Winnebago occurred in the early 1600’s. The Missouria settled farther south than did the Oto and Iowa. They are believed to have ascended the Mississippi and traveled overland to the mouth of the Grand River in the present state of Missouri. The Oto accompanied the Missouria to the Grand River site then continued up the Missouri River to form a separate group.

About 1730, a series of attacks by the Sauk and Fox forced the Missouria to move again, this time to within a few miles of a village of Osage. However, the attacks by the Sauk and Fox continued to decimate the tribes, and smallpox further depleted the group. An attack by Sauk and Fox in 1798 almost wiped out the Missouria, and remnants of the tribe divided and fled to other tribes for protection. Some joined the Osage, others joined the Kansa; but most sought refuge with the Otos on the Platte River in Nebraska. By 1819 the Missouria and Otos were considered to be one nation.

Although tradition says the Otos accompanied the Missourias and then separated, it is more probable that the Otos were more closely associated with the migration of the Iowa into the present state of Iowa.

The first Oto moved into southeast Nebraska along the Nemaha Rivers, and to the Platte River near Ashland in the early 1700’s. They soon adopted the earth lodges of their Pawnee neighbors, much as the Omahas and Poncas had done, since the bark lodges of their woodland days were impractical on the plains. They also planted crops suited to their new home, and adopted the Pawnees’ twice-a-year buffalo hunts to complete their adaptation to life on the fringes of the Great Plains.

By 1721 the Oto were reported to be living on the south bank of the Platte River where Lewis and Clark encountered them in 1804. From 1817 to 1841 the Oto and Missouria lived in four villages near the mouth of the Platte.

The Oto village consisted of from 40 to 70 earth lodges. The Otos gave much more importance to their village life than the nomadic life of the buffalo hunt. Men engaged primarily in hunting, while women tended to the children and lodge. Both worked in the garden, although the women did the greatest portion.

With the exception of personal property, everything belonged to the women, including the lodge, tipi, and all utensils pertaining to the maintenance of the household. The women also maintained control over all game brought home, and all garden produce. They also had the right to dispose of all properties.

Oto ceremonies were concerned with a male’s validation as a warrior, but it s clear that the Oto valued skill in hunting much higher than skill in warfare. A warrior’s ability to defend his people was considered to be of great importance, but a warrior who led offensive raids was thought to be endangering the group.

The Oto had hereditary chiefs, but their power was not much greater than other men of rank. The civilian chief’s main concern was for the welfare of his people and maintenance of peace. The chief was considered to be the head of the family, and the family was the most important aspect of social and ceremonial organization.

The Oto believed in a supernatural world and made offerings to Wakonta, who resided in inanimate and animate objects and was greatly revered. The supernatural world controlled all things, and controlled every aspect of the individual’s thought and behavior.

Oto medicine men, more properly called shamans, dealt with the supernatural world and with the business of healing the sick. The power of the shamans to cure and diagnose came through a vision experience , or was inherited. Members of the both the Buffalo Lodge and Medicine Lodge practiced curing, healing and exorcisms, while shamans independent of those lodges, were skilled in the use of medicinal herbs.

The Otos planted beans, pumpkins, corn and melons, and cultivated their crops at various intervals throughout the growing season. When the people returned from buffalo hunting, the corn would be ripe, but before it was harvested a feast was held by the Red Bean Medicine Lodge.

While the corn was growing, the Otos and Missourias began to formulate plans for the spring buffalo hunt. The Buffalo Clan provided leadership for the spring hunt, and the Bear Clan assumed leadership for the fall hunt. In 1935, William Whitman described an Oto buffalo hunt of 1874 as related to him by an old Buffalo Medicine doctor born in Gage County in 1863.

“In the spring the Buffalo gens (clans) got together and appointed a certain ‘good’ man, a man that knew how to be the leader. . . . We went south past Fort Hay, Kansas, fifty or sixty miles. This was where we ran into a lot of buffalo. You could see a bunch here and there, lots of them. . . . When they saw buffalo, the crier went round and everybody got ready, got guns and bows. When they saw the buffalo about a quarter of a mile away, nobody started until they whooped (the leader gave the signal). If anyone started before that, he got whipped. They killed as many as they wanted and then came back with horses loaded with buffalo.”

That was to be the last Oto buffalo hunt, since the hide hunters were rapidly slaughtering the great herds to the brink of extinction. Just seven years later, the Otos would be gone from their Gage County reservation to one in Oklahoma, displaced once more by a stronger, more numerous people.

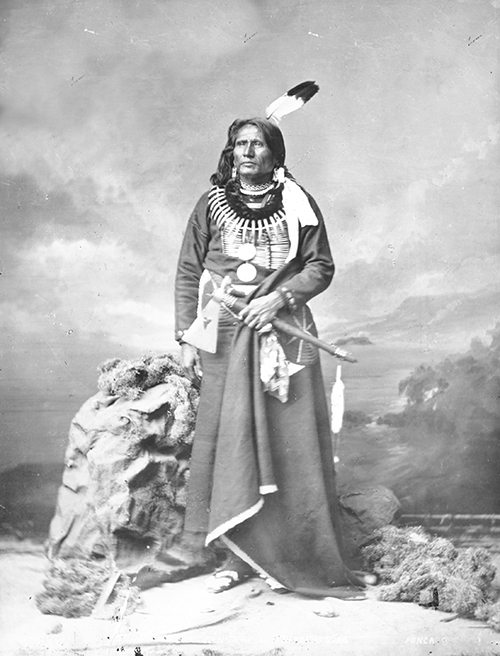

Sky Chief of the Pawnee Nation

Among the Pawnee chiefs was Sky Chief. Sky Chief had taken over for his father, one of the great Pawnee Chiefs, who by this time was old and infirm, and was no longer able to lead the annual buffalo hunt to Southwestern Nebraska.

Among the Pawnee chiefs was Sky Chief. Sky Chief had taken over for his father, one of the great Pawnee Chiefs, who by this time was old and infirm, and was no longer able to lead the annual buffalo hunt to Southwestern Nebraska.

Sky Chief had begun to make a name for himself among the Pawnee. He was a leading advocate of the “Accommodation” treaty with the U.S. Army. Under this treaty, the Pawnee supplied scouts for the Army, and guards for the transcontinental railroad, which at the time was pushing west across the prairie. In return, and most importantly for the Pawnee, the Army provided protection to the Pawnee Nation against their Indian enemies.

The summer buffalo hunt was the high point in the year for the Pawnee. The 1873 hunt was a massive affair, and was to prove to be the last of the great buffalo hunts. Sky Chief, Sun Chief, and Fighting Bear were the leaders of a great Pawnee expedition, perhaps numbering some 250 warriors plus 100 women and 50 children.

Their objective was to hunt buffalo along the banks of the Republican River, to what is now Trenton. The party was entirely peaceful, and it was a joyous time for the Pawnee. Nevertheless, when they reached the north bank of the Republican (at Trenton), guards were posted around the camp, as it was feared that there might be Sioux in the area.

Early in the morning of Aug. 4, 1873, the Pawnee hunters began their hunt, moving north, up the divide, between the Republican and Frenchman Rivers, followed closely by the women and children who processed the buffalo kills. Sky Chief had just killed a buffalo and was in the process of skinning the animal when an advance guard of a Sioux war party came upon the scene and killed him, thus beginning the battle that we know today as the Battle at Massacre Canyon.

As soon as the firing began, John Williamson, the white Indian agent who had been sent along with the Pawnee, to supervise the hunt, lend counsel to the Indians, and generally keep an eye on things, rode out to meet the Sioux, carrying a white flag of truce. He meant to bring a stop to the firing, by negotiating with the Sioux. When his horse was shot out from under him, he was forced to retreat and the battle was drawn.

It was not much of a battle. Massacre is an apt name. Sioux warriors, with a 4-to-1 advantage over the Pawnee, quickly joined the advance party. While Pawnee warriors, women and children dropped everything and fled down the canyon toward the Republican, Sioux warriors from the Brule and Oglala Sioux tribes rode along the ridges, on either side of the canyon, firing down on fleeing warriors, women and children. When the carnage ended, Sky Chief and 69 Pawnee warriors, women and children were dead (some reports say as many as 150), as the result of the Sioux attack. It is generally conceded that only six Sioux warriors died in the battle.

The Sioux broke off their attack as suddenly as they had begun, feeling that their objective had been accomplished. The Pawnee survivors retreated down the Republican Valley as quickly as they could manage, leaving behind some 500 hides and meat — their entire gathering from their summer’s buffalo hunt. They finally regrouped at Royal Buck’s Red Willow settlement, where they were met by a contingent from the U.S. 3rd Cavalry, out of Fort McPherson. The Army helped provide the survivors with food stuffs, and then accompanied them back to their reservation at Genoa.

The Battle at Massacre Canyon was an important event in the history of the west. It was the last inter-tribal battle in Nebraska. It signaled the last great buffalo hunt. It caused the Pawnee to give up their Nebraska reservation, in exchange for land in the Indian Territory. It caused the Pawnee to leave Nebraska, their traditional home, and move to the Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma.

…………………………

Sky Chief Spring Ranch

On the north side of Highway 6 & 34, between Cambridge and Holbrook, nestled into the trees as the base of the bluffs that rise from the Republican River is a home belonging to Joyce and the late Dr. Bob Spear.

Beside one of the spring-fed ponds is a monument, that in 1924, was dedicated to the great Pawnee Chief, Sky Chief, who would bring his hunting party to these springs, to set up camp for their annual buffalo hunt. The top of the bluffs has been called “Arrow Head Haven” because of the many arrow heads that turn up after a rain. To the east of Spears’ home, in the trees, there are strange mounds, marked as Indian Mounds by the Furnas County Soil Conservation Office.

The D.L. D. (Detroit-Lincoln-Denver) Highway passed close to the property, and in the 1920s there was a filling station on the south side of the highway, which featured refreshing, cool spring water for drinking and filling the canvas water bags that motorists hung on the outside of their cars, so that evaporation would keep the water cool.

In the 1930s, Dan and Margaret Dick expanded the attractions at “Sky Chief Spring Ranch.” Dick taught instrumental music at the Cambridge school, but in addition he built a large pavilion, for roller skating and dancing. The dances were popular and Mr. Dick often played with the dance bands that appeared there. Later, in cooperation with “The Village of Cambridge,” he put in a nine-hole golf course on 50 acres of pasture northwest of the farm buildings. This course was in use until Cambridge’s new course was built in 1975.

Spring Ranch, Sky Chief’s Campground, is a peaceful spot, and it is easy to imagine it as a welcome pause at a cool, restful oasis for Sky Chief’s Pawnee hunting parties, or hot and weary travelers, traveling west in trucks and automobiles, on a torrid August journey (with no air-conditioning!).

Source: Massacre Canyon, by Paul Riley, A Touch of History, by Jackie Johnson

Spring Ranch skating rink and dance hall was owned by the William Kottwitz family in the 1920s they also owned the gas station.

— Posted by kotty45 on Tue, Oct 2, 2012, at 3:57 PM

Native American Full Moon Names

Native Americans Full Moon names were created to help different tribes track the seasons. Think of it as a “nickname” for the Moon!

Why Native Americans Named the Moons

The early Native Americans did not record time by using the months of the Julian or Gregorian calendar. Many tribes kept track of time by observing the seasons and lunar months, although there was much variability. For some tribes, the year contained 4 seasons and started at a certain season, such as spring or fall. Others counted 5 seasons to a year. Some tribes defined a year as 12 Moons, while others assigned it 13. Certain tribes that used the lunar calendar added an extra Moon every few years, to keep it in sync with the seasons.

Each tribe that did name the full Moons (and/or lunar months) had its own naming preferences. Some would use 12 names for the year while others might use 5, 6, or 7; also, certain names might change the next year. A full Moon name used by one tribe might differ from one used by another tribe for the same time period, or be the same name but represent a different time period. The name itself was often a description relating to a particular activity/event that usually occurred during that time in their location.

Colonial Americans adopted some of the Native American full Moon names and applied them to their own calendar system (primarily Julian, and later, Gregorian). Since the Gregorian calendar is the system that many in North America use today, that is how we have presented the list of Moon names, as a frame of reference. The Native American names have been listed by the month in the Gregorian calendar to which they are most closely associated.

Native American Full Moon Names and Their Meanings

The Full Moon Names we use in the Almanac come from the Algonquin tribes who lived in regions from New England to Lake Superior. They are the names the Colonial Americans adapted most. Note that each full Moon name was applied to the entire lunar month in which it occurred.

| Month | Name | Description |

| January | Full Wolf Moon | This full Moon appeared when wolves howled in hunger outside the villages. It is also known as the Old Moon. To some Native American tribes, this was the Snow Moon, but most applied that name to the next full Moon, in February. |

| February | Full Snow Moon | Usually the heaviest snows fall in February. Hunting becomes very difficult, and hence to some Native American tribes this was the Hunger Moon. |

| March | Full Worm Moon | At the time of this spring Moon, the ground begins to soften and earthworm casts reappear, inviting the return of robins. This is also known as the Sap Moon, as it marks the time when maple sap begins to flow and the annual tapping of maple trees begins. |

| April | Full Pink Moon | This full Moon heralded the appearance of the moss pink, or wild ground phlox—one of the first spring flowers. It is also known as the Sprouting Grass Moon, the Egg Moon, and the Fish Moon. |

| May | Full Flower Moon | Flowers spring forth in abundance this month. Some Algonquin tribes knew this full Moon as the Corn Planting Moon or the Milk Moon. |

| June | Full Strawberry Moon | The Algonquin tribes knew this Moon as a time to gather ripening strawberries. It is also known as the Rose Moon and the Hot Moon. |

| July | Full Buck Moon | Bucks begin to grow new antlers at this time. This full Moon was also known as the Thunder Moon, because thunderstorms are so frequent during this month. |

| August | Full Sturgeon Moon | Some Native American tribes knew that the sturgeon of the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain were most readily caught during this full Moon. Others called it the Green Corn Moon. |

| September | Full Corn Moon | This full Moon corresponds with the time of harvesting corn. It is also called the Barley Moon, because it is the time to harvest and thresh the ripened barley. The Harvest Moon is the full Moon nearest the autumnal equinox, which can occur in September or October and is bright enough to allow finishing all the harvest chores. |

| October | Full Hunter’s Moon | This is the month when the leaves are falling and the game is fattened. Now is the time for hunting and laying in a store of provisions for the long winter ahead. October’s Moon is also known as the Travel Moon and the Dying Moon. |

| November | Full Beaver Moon | For both the colonists and the Algonquin tribes, this was the time to set beaver traps before the swamps froze, to ensure a supply of warm winter furs. This full Moon was also called the Frost Moon. |

| December | Full Cold Moon | This is the month when the winter cold fastens its grip and the nights become long and dark. This full Moon is also called the Long Nights Moon by some Native American tribes. |

Note: The Harvest Moon is the full Moon that occurs closest to the autumnal equinox. It can occur in either September or October. At this time, crops such as corn, pumpkins, squash, and wild rice are ready for gathering.

The Story of the Otoe

Article credit: From Nebraska Old and New by A.E. Sheldon—Copyright 1917

The article below spells Oto with an e on the end; it is reprinted as it appeared in the article.

The chief village of the Otoe tribe was in Saunders County at the junction of Otoe Creek with the Platte River, ten miles north of Ashland. It is at that spot that Highway No. 16 crosses the Platte today. They had fine gardens along the Platte, plenty of wood and water, and a noble hill for a lookout. Here was the capital of the Otoe, an earth lodge village of over one hundred houses. When Lewis and Clark came up the Missouri River in July, 1804, their scouts called there. It was there Moses Merrill, the missionary, and his wife found them in 1833. In 1835, the tribe abandoned this village and made a new village on the north side of the Platte. The location of this was eight miles west of Bellevue, where Moses Merrill and his wife had their mission school. In 1840, after the death of Moses Merrill, the Otoe moved their village again to the south side of the Platte, just west of Plattsmouth. In 1854, the Otoe sold all their land to the United States, except for one reserve ten miles wide, which extended twenty-five miles east and west on both sides of the Big Blue River in what is now Gage County. The tribe moved to this reservation in 1855. The Otoe built a wonderful Indian village there. It remained there until 1881 when the tribe sold this last Nebraska reserve to make homes for the white settlers. At that time they moved to Oklahoma where they now live.

The Otoe was a small tribe, never more than 2,000 people. Their language is a Siouan language. They are relatives of the Sioux, Ponca, and Omaha. Their stories tell of a long journey westward from the Ohio River to Nebraska. It was the Otoe tribe that gave the Indian name to the Platte River and thereby named our state. Among the noted men of the Otoe tribe were Itan or Chon-Moni-Case, greatest war leader of the tribe; Battist Deroin, a half-breed educated Otoe, and Nee-Scaw or Whitewater.

The story of Whitewater is one of the most interesting stories of Nebraska Indians. In 1864, a family of peaceable Otoe—man, wife, grandmother, and little children—trapping on a creek near the west line of the Otoe reserve, were surprised and all brutally murdered by white men. It was soon after the Cheyenne Indian raid along the Little Blue. The white murderers were never caught.

Nee-Scaw brooded over this murder. His Indian soul demanded revenge. He found two white men in camp and killed them both. For this he was, in 1872, tried and sentenced to the Nebraska State Penitentiary for life. He became a converted Christian and model prisoner. In 1859, he was pardoned by Governor Thayer. He returned to his tribe in Oklahoma. Here he spent the rest of his life in active good work, loved and honored by all who knew him.

Today, the Otoe Indians live with the Missouri Indians on a reserve which is just west of the Pawnee reserve in Oklahoma. Together they number about 750. For their home, they have a beautiful rich prairie bordered with timber.

Chief Standing Bear

A famous Nebraska Native American was Chief Standing Bear of the Ponca tribe. He sued the Federal Government and won. The book “I Am A Man” tells his story and his desire to bury his son in their native homeland along the Niobrara River in Northeast Nebraska.

OMAHA

AN OMAHA CHRONOLOGY

Article credit: From The First Voices – January/February 1984 NEBRASKAland magazine

The history of Nebraska’s Omaha people can be traced back to at least the 1670’s, but before that time, only archeology yields clues regarding their past. Archeology, however, has had little to tell about the tribe in earlier times.

According to tribal traditions, the Omaha homeland was the Ohio River Valley, but the archeology of that region is mute regarding the Omaha. It has been suggested that the Omaha (indeed, all the Dhegiha-Sioux speaking peoples including the Ponca, Quapaw, Kansa and Osage) can be included in the “Middle Mississippian” culture which flourished in the vicinity of St. Louis, Missouri, from about 800 to about 1400 AD. Although this is an attractive idea, there is no direct support for it. Another problem exists in that between about 1400 AD and the 1670’s, no archeological sites have been identified as early Omaha villages. These villages did exist once, without a doubt, but have been either destroyed, misidentified or remain yet to be discovered and credited as Omaha villages.

The Marquette and Joliet expedition of the 1670’s passed the mouth of the Missouri River, and from local Indian informants the explorers learned a little about the people who lived on the Missouri. The only information that survived, however, are the names of certain Indian groups on a map the explorers drew of what they had heard about. One of the tribes drawn on the map was the Maha, or Omaha. It is clear that by the 1670’s the Omaha had left the Mississippi River area and moved west onto the prairies along the Missouri. Just how many years prior to the 1670’s this move was made is not known, but it may have been as early as 1600 or even before.

In 1700, Pierre Charles le Sueur (who never saw an Omaha face to face but relied on others for his information) described the Omahas as living in a village of 400 dwellings, with a population of perhaps 4,000 people. This village is generally believed to have been located on the Big Sioux River (once called the “River of the Maha” below present-day Sioux Falls.

Sometime after 1714 – a good guess would be 1735 or so – the Omaha built a village on Bow Creek in Cedar County, Nebraska. After a factional battle between rival groups in the tribe, the Omahas moved to the spot where Dakota City is today, probably about 1750. Some have suggested that the intratribal battle on Bow Creek resulted in the splitting of the Ponca from the Omaha; however, it seems more likely that the Ponca had already split from the Omaha prior to establishment of the Bow Creek village, that is, priolr to about 1735.

The new village at Dakota City was occupied for only a few years. By 1765, the Omahas had moved several miles south along the Missouri River bluffs, and around 1755 they moved still a few more miles southeast to the spot where Omaha Creek leaves the bluffs, where the town of Homer was later established. Here, the Omaha built the “Big Village,” or Ton won tonga. This was the village of Black Bird, the most famous of the early Omaha chiefs (indeed, the first Omaha to be known by name). Under Black Bird the Omahas were a powerful military force and wielded great influence. Black Bird kept a strict rule over the Omaha people, and it is said he was greatly feared. Sometime, probably in the 1790’s he learned of the use of arsenic and took to poisoning anyone who opposed him. He himself fell victim to smallpox, along with perhaps 400 other Omaha, in 1800.

The Big Village continued to be occupied until 1819. After Black Bird’s death, a chief named “Big Rabbit” led the Omaha for a few years. The famous chief Big Elk, Ongpatonga, took over principal leadership of the Omahas around 1810. The Omahas were met at the Big Village by many American fur-trading and exploring expeditions of the early 1800’s until wars with the Sauk and Fox drive them away.

In 1819 the Omaha people moved to the Elkhorn River where they lived until 1834. In 1815 and 1825 they made treaties of peace and friendship with the U.S., but no lalnd was relinquished by these. In 1828, half the tribe, under Big Elk, moved back to the Big Village on the Missouri, but were driven back by the Sauk and Fox within a year. In 1830 the Omahas signed away their claims to lands in Iowa by virtue of the Treaty of Prairie du Chien. A year later, the Omahas suffered another smallpox attack, and finally, the tribe moved back to the Big Village in 1834.

The Omahas remained at the Big Village until 1842. In 1836 they signed a treaty relinquishing claims to lands in present northwest Missouri. After several battles with the Lakota, who replaced the Sauk and Fox as the principal foe of the Omaha in the late 1830’s and 1840’s, the Omahas moved to the mouth of Logan Creek on the Elkhorn in 1841, where they lived for two years under miserable conditions. In 1843 they returned to the Big Village and again were attacked by the large parties of Lakota, and abandoned Ton won tonga for the last time late in 1844, moving to a village on Papillion Creek just west of Bellevue, Nebraska. They numbered about 1,300 at this time. They relinquished all their lands save for a reservation in northeast Nebraska, in Thurston County.

Saux and Fox Indians

Article Credit: From The First Voices – January/February 1984 NEBRASKAland Magazine

They called themselves the A-sau-we-kee, Yellow Earth People, and Mes-qua-kee, Red Earth People. We know them as the Sauk and Fox, a loose confederation of two formerly separate tribes forced together for survival, and now living primarily in Oklahoma and on a small tract of land along the state line in Richardson County, Nebraska and Brown County, Kansas.

Algonquian-speaking people, referred to by the French as “People of the Fire,” the two tribes originally lived in the Great Lakes region. By the middle of the 17th century, both tribes were under heavy pressure from their Indian enemies and from the French. In nearly continuous warfare they suffered tremendous losses, and by the early 18th century had formed a loose alliance and began a gradual movement southward.

The allied tribes established villages along the Mississippi, but white settlement in the area was increasing, and conflicts between the tribes and the whites continued. Pressure for their removal grew, and their position was further weakened by the defeat of the British in the War of 1812, which cost them an important ally.

Following the war, unrest continued, culminating in the Black Hawk War of 1832, when the Indians, led by their aging chief Black Hawk, attempted to return to Illinois. They met fierce resistance from the Illinois militia, and the battle became a massacre.

The remnants of the two tribes retreated to Iowa, fought with the Dakota, and finally, in 1845, gave up all claim to holdings east of the Missouri River. That year signaled the end of their Woodlands life, for the Kansas prairie they were to occupy at the Osage River Agency was vastly different from the land they had known.

Migrations continued for some two decades, and the people struggled to maintain their old ways of life. But, severely weakened by years of warfare, the ravages of disease, and the curse of alcohol, they succumbed to the pressure for removal, and in 1886 the remnants of the band were escorted by calvary to Oklahoma Indian Territory. In 1869 the government set aside the Nebraska-Kansas Reservation where a few families still live. That small reservation adjoins that of the Iowa Indians, a Siouxian-speaking displaced Woodlands tribe. The Iowa, too, were removed to Oklahoma, but individual families still hold land in Nebraska granted to them in 1885.

As a Woodland people, the Sauk and Fox lived in villages of up to 100 large lodges 40 to 60 feet long and about 20 feet wide. The lodges were covered with elm bark in the winter, and with grass mats in the summer.

Both tribes grew vegetables, gathered wild fruit, and held annual buffalo hunts which took them as far west as Kansas. They trapped game as well, and by the 1700’s had developed an active trading relationship with European traders. A few villages located on a productive lead vein annually traded up to 4,000 pounds of smelted lead to the Europeans.

A strong system of hereditary clans and two larger social orders, a soldier society and a buffalo society, dominated the tribes’ social organizations, and the major religious ceremonies of the Saux and Fox were clan festivals including thanksgiving and harvest festivals which followed the pattern of other agriculture groups in North America.

Passing of the Otoe Indian Reservation

By C. D. Clements, Lincoln Sunday Star newspaper article dated May 17, 1925

It should be noted that all references to the Otoe Reservation have the word Reservation capitalized. The article spells Otoe and Missouri which really should be Oto and Missouria.

The Otoe and Missouri Indian Reservation, a feature of respective awe, interest and curiosity to settlers in the early days in southern Gage County, and now an item of real history, has passed. The land is left, and covered with sturdy white men, but all the Indian landmarks have disappeared. True, we have the “Reservation Line,” running practically east and, west through sections in the townships of Elm, Sicily, Wymore and Island Grove, in southern Gage County, to forever recall the matter of the Indian Reservation to the mind of future generations, and, it is conceded by a careful check, that about two out of every seven hundred of the present citizens of Gage County can vividly narrate real first hand dealings with the Indians of the extinct Reservation. There is coming a time, perhaps in the next decade, when no one will be left of the generation which touched elbows with the red men of Gage County. We also have “Big Indian Creek,” which rises in the southwestern corner of the county, and flows to the Big Blue River at a point just southeast of Blue Springs, which derived its name from the red men who inhabited its banks in the early days.

The Otoe and Missouri Indian Reservation, a feature of respective awe, interest and curiosity to settlers in the early days in southern Gage County, and now an item of real history, has passed. The land is left, and covered with sturdy white men, but all the Indian landmarks have disappeared. True, we have the “Reservation Line,” running practically east and, west through sections in the townships of Elm, Sicily, Wymore and Island Grove, in southern Gage County, to forever recall the matter of the Indian Reservation to the mind of future generations, and, it is conceded by a careful check, that about two out of every seven hundred of the present citizens of Gage County can vividly narrate real first hand dealings with the Indians of the extinct Reservation. There is coming a time, perhaps in the next decade, when no one will be left of the generation which touched elbows with the red men of Gage County. We also have “Big Indian Creek,” which rises in the southwestern corner of the county, and flows to the Big Blue River at a point just southeast of Blue Springs, which derived its name from the red men who inhabited its banks in the early days.

The Reservation which contained these Indians was ten miles wide, north and south, and twenty-five miles long, east and west. It lacked two and one-fourth miles of reaching the east line of the present Gage County, and extended west into Jefferson county two and three-fourths miles. From the Kansas-Nebraska state line it extended north eight miles, and south into Marshall and Washington Counties, Kansas, two miles. The northern boundary came close to the present city of Wymore…but Wymore was not there. It came to within two and one-half miles of Blue Springs — and Blue Springs was there and thriving just three years after the creation of this Reservation by the United States Government. It will be seen, therefore that this Reservation contained 250 square miles — 250 sections – of fertile land, 160,000 acres, of which 126,720 acres were within Gage County, well watered and drained by the Big Blue River, Big Indian, Wolf, Plum, Mission and other creeks, and contained thick tracts of timber and provided “happy hunting grounds” in plenty for the red men.

Created by Treaty

The treaty which created the Otoe Reservation and congregated the Indians from other parts of Nebraska to within its boundaries was drawn March 15, 1854. It was signed by Franklin Pierce, then President of the United States. The Indians came to the Reservation from Nebraska City, which was then in Pierce County, named after the President. It was later named Otoe County, after the Indians who had left it forever. At this time Gage County did not bear its present name. A county had been laid out from the west line of Richardson County, extending to the Platte River on the north, and the Rocky Mountains on the west, to be known as Jones County. Nebraska was a territory, with the seat of government at Omaha, and Francis Burt was functioning as the First Territorial Governor. Mr. Burt died in the Old Mission House, at Bellevue, Nebraska, October 18, 1854.

During the first session of the legislative assembly of Nebraska territory, at Omaha, in 1855, an act was drawn to locate and bound “Gage” county, and locate a “seat of justice.” In conferring a name upon the new county it was the intention of the historic assembly to honor the Rev. William D. Gage, a Methodist minister, then serving as chaplain of both houses of the assembly. The county was designated as being 24 miles square, and contained the south sixteen townships or the south two-thirds of the present Gage County. The act became a law March 16, 1855.

Not A Single Settler

At the time the name of “Gage” was bestowed upon this portion of the public domain, there is not known to have been a single actual settler within its boundaries, and it is doubtful if at that time there was a single white person in the county. It was, in fact, more than two years after the passage of this act before a sufficient number of settlers had gathered in the new county to attempt its organization. No evidence is known to exist which shows that a commission charged with the duty of locating a county seat for the new county ever met or acted under the authority thus conferred upon it. However, at a third session of the territorial assembly, at Omaha, in January, 1857, an act was passed and approved locating a “seat of justice” for Gage County at “Whitesville.” A town site was staked out. No one came to boom it. The location was in what is now Rockford Township, in the southeast quarter of section 29, just a little southeast of the present town of Holmesville, and practically in the center of the county as originally laid out. It is said that for three or four years thereafter stout oak stakes driven into the original prairie soil to designate corners of lots in the new county seat were plainly visible. Finally they were destroyed by prairie fires and all trace of the hopes of “Whitesville” disappeared.

Blue Springs, a settlement which sprung up two and one-half miles north of the reservation in July, 1857, was an aspirant for the county seat, and at an election held in August, 1857, received a majority vote as the location of the seat of government, but the election was not legally ratified, nor did the elected officers qualify properly, and the project died without action, there being less than fifty white settlers in the county at that time, as near as can be learned from records. The first officers of Gage County elected were: Daniel P. Taylor, sheriff; Calvin Miller, treasurer; John Hart, recorder of deeds; N. B. Belden, superintendent of schools. Each failed to quality, and all later were legally superseded. At a meeting held at the home of Albert Towle, in Blue Springs, October 7, 1858, Albert Towle and H. M. Reynolds were chosen as County Commissioners, and Nathan Blakely as County Clerk. These men are buried in the Beatrice cemetery.

Beatrice, which had been founded by early settlers coming from Nebraska City by steamer and horseback, about the time of the founding of Blue Springs, was contending for the county seat, and to terminate the dissension that grew out of this rivalry in the early days of Gage County, the territorial legislature at its assembly December 5, 1859, in Omaha, passed an act to legalize the first organization of Gage County, which was a technicality on which Blue Springs also hinged its right to the county seat, and the seat of government was located at Beatrice. The passage of this act forever destroyed the hopes of Blue Springs relative to securing the county seat, and it has since remained at Beatrice.

Also at the first territorial assembly in Omaha, March 6, 1855, “Clay” county was created and defined as containing the present north third of Gage and the present south third of Lancaster counties, making Lancaster, Clay and Gage each 24 miles square. It was provided that a place to be called “Clatonia” would be the county seat, but no evidence is known to exist to show that any place was ever selected by the legislative commission as a county seat for Clay County. There was no town in Clay County while it existed, and nothing is recorded but a small settlement called “Austin’s Mill” after the name of the first settler in 1857 near the present village of Pickrell. The mill soon played out and the settlers moved away. On February 15, 1864, a bill was passed by the territorial assembly providing for the division of Clay County, attaching the north half to Lancaster and the south half to Gage County, making them as they are present, and thus Clay passed away.

Ranks Thinned by Disease

The Otoe Indians were a small tribe of Sioux stock, formerly holding territory west of the Missouri River and south of the Platte. They are mentioned by many of the early French explorers in America from 1673 to 1750, as being located in what is now Iowa, Illinois, Wisconsin and Missouri. History states that they were located along the Platte River, in what is now eastern Nebraska, in 1761. Here they were found by the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1804. Having been greatly diminished in number by war and disease, in 1817 they came to the Pawnee Indian locality, near the present city of Fremont, where they lived for a time and were federated with the Missouri Indians, another small and friendly tribe, who spoke the same language. For 25 years they lived between Fremont and the mouth of the Platte River, and in 1841 removed to near Bellevue. In 1845 they were removed to a reservation near Nebraska City, which land was ceded to the United States for settlement in 1854, when the Otoes and Missouris were removed to the Reservation created for them in southern Gage County. In 1798 the tribe of Otoe Indians living in what is now Iowa and Missouri, and numbering about 1,250, were driven across the Missouri River by a hostile band of Sauk Indians. In 1823, decimated by smallpox until they numbered but 80 souls, this band of Otoes moved with the Otoes from near Fremont, and occupied the south Platte territory.

Therefore, we find that there were about 1,300 Indians on the reservation near Nebraska City. Authorities in 1854 state about a thousand were transferred to the Gage County Reservation. In 1859 their number is given in history as 900 . In 1862 the Otoe and Missouri’s south of Blue Springs totaled 708; in 1867, 511; in 1877, 457 and in 1882, when they were removed from Gage County to Oklahoma by the government, they numbered 334, and are now said to count 332.

A report made by George Heppner, the government agent for the Otoe and Missouri Indians, who came to the Gage County Reservation with the transferred tribes, under date of November 1, 1855, to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Washington, D. C., contained the information that the Indians were then occupying their new reservation in Gage County, and that a crop of corn had been raised for their support that season. This, therefore, appears to have been the first breaking of soil, and raising of a food crop in Gage County. Heppner is recorded as being the first white man to enter Gage County.

The writer has recently had personal interviews with Francis M. Graham, now 81 years old and residing in Blue Springs, one of the very first settlers in that town, coming in 1859 to the small log cabin settlement out of which Blue Springs later sprung; with Mrs. Ameila Wilson, nee Amelia Darner, widow of Robert A Wilson, influential, early settler and founder of Blue Springs, now 86 years old, and still residing in Blue Springs; and with Fred H. Barnes, now residing in Barneston, son of the late Francis Marion Barnes, and Mary Dripps-Barnes, pioneer family of Barneston, after whom the town is named; and from these sources has been able to glean considerable history and information relative to early life and the Indians in Gage County that is authentic and should be of vital interest. Much history is also supplied the writer by Mrs. Carrie Lott-Crawford, now living east of Wymore, the first white child born in the Blue Springs early log cabin settlement, widow of James Crawford, Civil War veteran and Indian fighter; from various other scattered early authorities and from records.

The above authorities recall vividly many occurrences, habits and dealing with the Indians; of early features and conditions in southern Gage County; of early animal life; and of the hard struggle of early settlers.

Buffalo Were Common

Buffalo were common in considerable herds in what is now Gage County before 1850, but with the coming of white men the animals were driven westward, and it is recorded that the Otoes in their regular fall hunt in 1855, had to go west of Jefferson county, and even to Decatur County, Kansas, to secure buffalo meat and hides. This was an annual hunt in which most of the male members of the tribe took part, and required several weeks. Other animals said to have been common to this section in 1855 were deer, antelope, fox, lynx, wolves, and bears. Rattle snakes were very common. Practically all of these reptiles that are now found in Gage County are in the hilly and rocky country, which was embraced in the last of the Otoe reservation – in the Wymore, Liberty, Barneston vicinity. The fowls common in 1855 were wild turkeys, quail, and great flocks of prairie chickens.

Grasshoppers were the most devastating insects of the early times. The first visitation of this pest recorded in history was in 1857 in Nebraska territory. The incident was described in print in the “Brownville Advertiser,” the best Nebraska newspaper of that time, as “moving the prairies.” The worst invasion known to history, and it was not then confined to Gage County, occurred on July 16, 1874, and there will be several who will recall this catastrophe. It is recorded that crops that July had the most excellent and promising outlook of any previous year. The first intimation of an impending disaster was when an occasional grasshopper dropped, seemingly out of the sky. Presently more dropped. The locust-hoppers began to get unusually thick. Observers glancing toward the sun beheld the sky full, to the depth of a solid half-mile or over, of a united, thick mass of the flying insects, moving with a slight wind and their wings glittering like mica. As the wind changed or slowed down the greedy hoard descended at once and the ground was immediately covered with a seething mass of flying, crawling, hopping, creeping, sputtering, nasty hoppers. Everything that was soft and green perished. The leaves on the trees, the prairie grass, all weeds, all crops, and all roots of all descriptions as far as they could be reached by the hoppers, were devoured. Corn fields were mowed down. Orchards were stripped of fruit buds, leaves and even bark. They are said to have slicked rails so trains could not run. But southern Gage County had no railways in that day, only a branch line of the Burlington extended from the north as far as Beatrice.

Lost His Cabbage

Joseph Lang, early settler living over the state line south of the Otoe reservation boundary, told of foreseeing the coming of the hopper scourge by the scattered “advance guard” which preceded the main body. He had a prize patch of cabbage, about an acre, which he had tended well, and which was heading up. He placed straw over the patch about two feet deep, thinking to have the heads. When the hoppers had departed he forked the straw off to find the cabbage heads and even the stalks eaten to the ground. The hoppers went right through the straw. They also ate up a patch of tobacco which he had leafing out.

Nor was this the last of the hopper scare. After the pests devastated the crops in 1874 and left, great alarm was stirred up the following spring by the discovery of millions of hopper eggs deposited under stones, in the ground, on dead timbers. Everything was covered with square inches of them in solid masses like fish eggs, only smaller, and they began to hatch, and move and fly about. They appeared in droves and hoards, and the young fellows were ravenous. ‘Twas in May, 1875, and everything was looking green, but it began to look blue to the early settlers.” In June, 1875, a south wind brought myriads of millions of the hoppers to southern Gage County and things began again to perish, and business came to a standstill. The settlers in downcast little groups were discussing a possible means of combating the hoppers when Providence intervened and saved the country. Settlers noticed that although billions of hoppers sat in their gardens and fields they seemed to have quit eating. Investigation at several places showed that every hopper was the victim of a species of boring beetle, infinitely small, of unknown origin, which attacked and drilled the hoppers through the body. They never flew again. They sat and died where they were. It is said that tons and tons of dead hoppers were washed into ravines and drift places by the first rain, and their bodies decayed and enriched instead of devastating Gage County.

The Otoes seemed to have cared but little about the hoppers. That was the white man’s burden. Uncle Sam was keeping the Otoes. Their chief worry was the loss of their buffalo herds to the westward plains.

The chief of the combined Otoe and Missouri tribes of Indians here in 1855 was an inveterate warrior called “Ar – ka – ke – ta.” He remained a chief under the administrations of George Heppner and William Dennison, as government agents on the reservation, and was removed in 1870 by Albert I. Green, then Indian Agent, because the old chief refused to obey orders of the agent, and live in a “frame dwelling” and do a little work. “Ar – ka – ke – ta” was a polygamist, valuing his wives according to the work they did. He was succeeded by “Shunga – monco,” meaning “Medicine horse,” who moved into the “white man’s house,” and after considerable parley the new chief helped saw logs for more houses. What finally became of old “Ar – ka – ke – ta” is not recorded, but it is probable that he now rests in his grave at the reservation in Oklahoma.

Origin of “Nee – haun – chee”

The Otoe Indian name meaning “Blue River,” is “Nee – haun – chee,” and this is where the party of nature-loving Beatrice residents, who formed a camping and outing club several years ago, and spent the summers on a fine grassy plot on the Blue River about eight miles northwest of Beatrice, got the name for their club.

It is claimed that in the very early days the Indians had no horses or ponies, but used as their only burden bearers, a large and tamed species of the present wolves. French and Spanish explorers two hundred years ago imported horses for their use, many of which fell into the hands of the early Indians, and ever thereafter the herds multiplied and thus came the fleet Indian ponies of a few decades ago, and many present day dogs are descended from the Indian domesticated wolves, it being a matter of common knowledge that the dogs invariably found with the Otoes about 1860 and 1870 possessed much higher developed and keener senses of detection, and more wolf traits, than the present day dogs.

With the passing of the Homestead law January 1, 1863, the ending of the Civil War in 1865; and the consequent westward movement of the white men, and extension of the railways in the early ‘70’s, land around Blue Springs and this vicinity began to have a value. It was even possible to find an occasional capitalist, who would loan a few hundred dollars on land, taking what is now the most common thing in the world – a mortgage, as security. The Otoes were dying out and their 160,000 acre Reservation was thinly populated, and a clamor was set up to open the lands for settlement.

Algernon S. Paddock of Beatrice, U. S. senator in 1875, introduced a bill providing for the sale of the west-three-fourths of the Otoe and Missouri reservation. The act was signed by the Department of Interior under President Grant, and by the Otoe Chief, and became a law August 15th, 1876, and the lands affected were appraised and sold for cash to actual white settlers, no more than one quarter section going to any one settler, and we secured the sturdy German, Bohemian, Irish and native farmers in southwestern Gage and southeastern Jefferson Counties who today are there in person, or through their succeeding generations. The lands sold for an average of $3 per acre. They are worth $150 today. The sale netted the Indians about $300,000 and they were on friendly terms with the white men and perfectly willing to be confined to their reduced east one-fourth of the original reservation.

Additions to the plat of Beatrice, and a hotel there, are named after Senator Paddock, as well as a Gage County Township, cut out of the sale lands. Mrs. O. J. Collman, of Lincoln, and Frank A. Paddock of Kansas City, are surviving daughter and son of the senator.

The Reduced Reservation

Thus it happened that after spending 22 peaceful years on the 160,000 acre Reservation first set aside by the government in 1854, the Otoe and Missouri Indians made their last appearance in Gage County on a reduced Reservation, a tract containing 70 square miles, or 44,800 acres, Blue Springs being the closest while settlement and the present town of Barneston being almost the exact center of the Reservation, and the Indians enjoyed six more years of happiness and considerable comfort before they were finally and forever removed by the government from the Reservation here to one near Red Rock, in Noble County, Okla., then Indian Territory in 1882, and where the survivors and descendants still live.

The Reservation of 1876 was ten miles north and south, still extending the two miles into Kansas, and was seven miles east and west. The northeast corner was in Section 27, Island Grove Township, two miles north and one and one-fourth miles west of the present village of Liberty, on land owned by William A. Stahl, Wymore banker. The northwest corner was in Section 27, Wymore Township, one and one-half miles east of the present city of Wymore, and two and one-half miles south of Blue Springs, on land then owned by James Crawford, and still owned and occupied by his widow, Mrs. Carrie Lott-Crawford. The southeast corner, in Kansas, was on land then owned by John Schmidt, now held by the Bank of Liberty. The southwest corner, in Kansas, was on the Ed Oates land, now owned by T. J. Reimann.

The government, from the first in 1854, had maintained the main works of the Reservation on land at the junction of Plum Creek with the Blue River, about one mile directly south of where Barneston now stands, and the principal Indian village was just north of this spot, and in 1876, with greater concentration, more importance was lent to the spot. Here was located a steam saw mill, where the Indians “earned their daily lumber,” a grist mill, where grain was ground to make jolly good “johnnie-cake,” a blacksmith shop, where Otoe ponies were shod, and vehicles and utensils repaired. The Otoes hunted, fished, and canoed the Blue, the squaws farmed and gardened while the bucks assisted their white overseers, whose duty it was to teach them to work in the various industries and to school and civilize them as best they could.

The First Indian Agent

George Heppner, of Nebraska City, was the first government Indian agent of the Otoes in Gage County, coming in 1854. The second agent was William Dennison, also of Nebraska City, who took charge in 1859. In 1869 Major Albert L. Green, of Pennsylvania, was appointed Indian agent by President Grant, and he remained for seven years. He did much to assist the Indians at a trying time, could converse with them fluently, and many improvements were added during his reign. He still lives and is a resident of Beatrice, additions in that city having been named after him. A later Indian Agent was Jesse W. Griest, whose wife, Sybelia, was an instructor in the Indian school, near where the Otoe Consolidated School in Barneston now stands. The consolidated school derives its name from the Reservation tribe. The Indian school was a large squatty frame building, erected in 1870 and school was held until the Indian removal in 1882. The building stood on land now owned by the C. C. Knapp estate, and was sold, bisected and removed in 1915. Nothing more remains. The building was of soft pine, which was hauled by teams from Beatrice, 22 miles.

The very first teachers in the Indian school were Miss Maria Van Dorn, Mrs. Nannie Armstrong, Mrs. Dallie Ely and Miss Elizabeth Walton. The first two were natives of Virginia, and are said to be buried in that state. Mrs. Ely, a Quaker, is buried in Kansas City. The late Z. H. Moore, pioneer resident of Oketo, Kansas, at the south line of the Reservation, was the Reservation Carpenter from 1870 to 1878. His wife, Mrs. L. G. Moore, of Oketo, was the Reservation Seamstress in the early days, and taught the Otoes how to dress. Mrs. Moore and two sons now own the Oketo State Bank.

Miss Phoebe Oliver, a Quaker, was the government appointed doctor for the Otoe women in 1870, and advised them for many years along the lines of modern and sanitary living and dress, and did much to aid them in disease. It was an old belief among the Indians that sickness and disease was caused by “evil spirits.”

In 1872 “white men’s clothes” were attempted on the red men, Calico and clothing were introduced by the government and donated by Quaker societies in the east, and fitted at the direction of the Reservation Seamstress. Gradually the men were induced to wear clothing furnished in this manner, but many of the older bucks could never be converted, and others often cut and destroyed the trousers furnished them, so they would not have to be worn, claiming that the legs made them too warm.

By about 1873 fully thirty-five families on the Reservation had tried the “experiment” of living in frame houses, built under direction of the Reservation Carpenter and other officers. Although statistics showed that this saved the Otoes many colds and consequent deaths, some of them could not reconcile themselves to the new mode of living.

Robert A. Wilson, early settler and founder of Blue Springs, was anointed by Agent Dennison in 1859 , as superintendent of work at the Reservation village, and for several years he had charge of the saw mill, managed the grist mill, and assisted with the Indians. He could converse fluently with the Otoes. He died at Blue Springs in 1919, at the age of 86. His widow, Mrs. Amelia Darner-Wilson, now 86, still lives in Blue Springs, as does a daughter, Mrs. Ella Swiler.

Pow Wow – A link with the past

Perhaps the most visible manifestations of Indian heritage are the Pow Wows celebrated throughout the country. These celebrations, with their singing, dancing and native dress, preserve a link to the past and affirm Indian traditions for new generations.

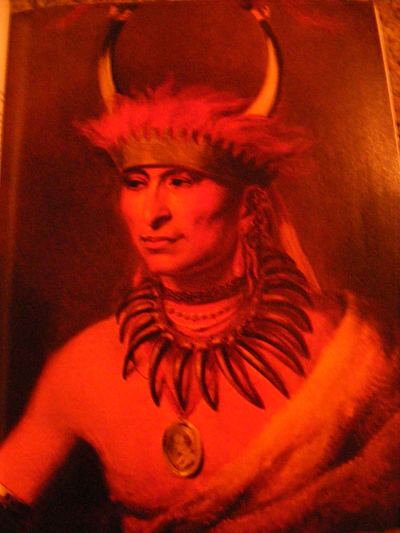

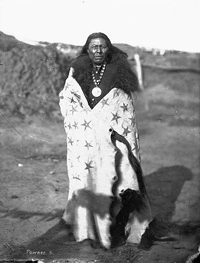

At the 1983 Omaha Tribal Pow Wow at Macy, ties to the past were more direct than usual: the Omahas heard songs actually sung by their ancestors; men born in tipis and earth lodges, and raised in the old culture. The songs, recorded at the turn of the century by ethnologists, had been stored, on old wax-cylinder records, by the Nebraska State Historical Society. In 1967 the cylinders were taken to the Library of Congress where the sounds were transferred to modern tapes; these were played at the 1983 Pow Wow. One of the early ethnologists, Mr. R. Gilmore, photographed Lone Buffalo (in picture) apparently recording a corn song or ceremony.

Tradition also inspires the Winnebago Pow Wow, which commemorates the homecoming of Company A, 34th Nebraska Volunteers. Under Chief Little Priest, these 75 warriors enlisted, to help the Army quell an uprising of Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho on the northwest plains in 1866. Little Priest, severely wounded, died after the unit was mustered out in 1867, but the American flag given him by grateful U.S. authorities, was raised at the scout’s homecoming celebration.

Today, many U.S. flags fly over the Winnebago Pow Wow, each representing deceased Winnebago veterans of U.S. military service. Like the warriors of old, veterans are accorded special honor among the Winnebago and other tribes, and the Winnebago Pow Wow, like many other Indian celebrations, is a festival of both native traditions and patriotism.

Above information taken from the 1984 “First Voices” NEBRASKAland published by the Nebraska Game & Parks Commission

On June 16, 2016 the Dance of the Summer Moon was held at Indian Cave State Park near the Nebraska Kansas border. This was made possible through the encouragement of Southeast Nebraska Tourism Council members, Byway 136 members, the work of Jan Alexander, Chairperson of Indian Cave State Park and lodging tax monies from Nemaha and Richardson Counties. For the past six years, the Southeast Nebraska Tourism Council has been working to make Native Americans, their culture and traditions more visible to the public. They started publishing Native American information in the 2014, 2015 Travel Guide and on their website. The Native American information is also available on the Byway 136 – Heritage Highway website – heritagehighway136.com.

Red Cloud

“Whose voice was first sounded on this land? The voice of the red people who had but bows and arrows……..”

With these simple but eloquent words, Red Cloud stirred the conscience of the country. Whether he realized it or not, he spoke not only for his Ogalala band, nor even the Sioux Nation: that day in Washington in 1870, he spoke for all the people of his race.

“This land,” whether we take it to mean Nebraska, or the Great Plains, or the entire continent, was all once the Indian’s own. In 1822, when Red Cloud’s voice first sounded, “at the forks of the Platte” according to his own account, white men were found on the Plains only at a few remote camps scattered hundreds of miles apart. When he died 87 years later, his people were impoverished and imprisoned on but a fraction of their land, while the whitepeople had the rest. The story is not a new one, nor is it exclusively Red

Cloud’s or his people’s. All of the Native American people experienced years of warfare, oppression and deprivation at the hands of the whites.

However, the story has been told so many times that it is often the only one about Indians that many people know. But, there is more to the Indian’s story.

It has been at least 12,000 years, and some say many, many times that number, since those very first voices sounded on this land, voices perhaps raised in the excitement of the chase as bold hunters with nothing but spears pursued brawny mammoth and giant, ancient bison. Since that time, this land has heard the ceremonials of farming people, the din of mounted hunters and milling buffalo, shrill war cries of brave men fighting their people’s enemies, red and white. And, of course, the lament of the vanquished from Red Cloud’s generation also sounded here. Then for several generations, the voices seemed to fall silent.

Today, however, the voices are being raised again. Some of them shrill and insistent, other patient and moderate, theses voices are telling again of wrongs past and present, of problems their people face today, of possible solutions to these problems. And, with renewed pride, they are telling themselves, their children, and the entire society, of the glories of their people and their traditions of Indian culture and Indian character that remain worthwhile today in both the Indian and non-Indian world.

It is all these things that the issue “The First Voices” is about. “The First Voices” was the January/February issue of NEBRASKAland magazine published by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Of course, it is not even remotely possible to tell the whole story of Nebraska’s Indian people. But, the story is being told elsewhere, often by Indian people themselves. And from these people, the descendants of the First Voices, there is much that can be learned —about Indians, and about our entire society. Their voices will continue to sound across this land more and more in coming years. Perhaps it is time they were heard!!!

Article Credit: Reprinted from “The First Voices” – January/February 1984 published by the Nebraska Game & Park Commission

Dance of the Summer Moon – 2016

In 2016, Indian Cave State Park hosted Dance of the Summer Moon, an exhibition of Native American Dance and Music. The event’s schedule is listed below.

April 23, 2016: At Sage Memorial Building in Brownville. Featuring 59 Rinehart prints of Native Americans taken at 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha & Indian Congress; Nebraska Governor Furnas as Indian Agent.

May 20, 2016: Schoolhouse Art Gallery in Brownville — Medicine Women by Princella Parker and Christine Lesiak — A documentary about the story of Native American female doctors such as Susan La Flesche Picotte.

June 2 – June 28, 2016: Schoolhouse Art Gallery in Brownville — Artist Paul High Horse display

June 18, 2016: “Dance of the Summer Moon” and Buffalo Cookout at Indian Cave State Park

(Native American dancers, singers, and drummers will perform and give presentations. Audience participation welcomed as well as lawn chairs)

Jan Alexander, Indian Cave State Park, 402-883-2575

The Eternal Tipi

By George P. Horse Capture – Plains Indian from “The First Voices” 1984 NEBRASKAland magazine

My people, the Gros Ventre, northern relatives of the Arapahoe, called them Tom Tenin, and the Omaha say Ti. But the Sioux word “Tipi” meaning “used to live in,” is the way they are now known through throughout the world. The glorious, special Tipi comes to us across the centuries, a gift, no doubt, from the Creator.

Long ago the people moved innumerable times, hunting and gathering as they entered a land where no one had walked before, The harsh terrain and weather in this new world forced the First People to experiment, adapt, revise and ultimately to produce many items vital to survival including the tipi.

After many years of experimentation, the value of the lightweight, conical, skin-covered “house” was proven. Leaning support poles against each other to form a cone is a natural, basic way to enclose an area. When anchored to the earth in the center, this framework becomes very strong, and there is no need to dig. The base has a sacred, circular shape and the poles seem to hold up the cosmos like the trees on a mountain. The structure becomes very special and symbolic.

It is practical and efficient, as well. It is clear that the inverted cone requires less heat because the space gets smaller as it gets higher, and the rounded surface parts the wind smoothly rather than fighting it. The diminishing outer-bottom edges provide ideal storage space, and the adjustable “ears” or smoke flaps control the air flow. Other Indian tribes who lived in different environments invented other structures that best suited their needs, but for the Plains Indians, it was and is the tipi.

Long ago, thin, tanned buffalo hide was preferred for the cover, and lodge pole pine for the poles. The decline in the availability of traditional hides and the higher efficiency of cloth made canvas the predominant tipi cover material by the later 1800’s, but the poles remain the same.

Tipis are Indian and Eternal. One can walk on the prairie today and still see the signs they left from long ago. These circles of stones called “tipi rings” cover the Plains area, and many of them undoubtedly held down the edges of the lodge cover in winter. These grand lodges made outstanding painted murals, where artists recorded brave deeds, dreams, world views or other special scenes. But, like all special things, painted tipis have always been rare.

A distinguished Indian Lady, at a naming ceremony on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation a few years ago, rose and spoke with deep emotion to the crowd: “With so many people in the world,” she said, “Indian people must always maintain all that we can that is Indian. One special thing that we have in common as a people is the beautiful tipi. If we wish to remain a special people, we should always try to camp in tipis because this ancient home is ours and will protect us and give us power as a people.”

No Indian celebration is complete without some tipis in the camp circle. Like beacons, these tipis are still lighting up the prairie. They are bright, they are beautiful, they are Indian.

Like the Indian people and buffalo, the tipis were never really eliminated – they were just sleeping. Like all of us, they endure through history, and, from the tips of our lodge poles, streamers still wave gracefully over our eternal tipis.